Unlike some tourist destinations, such as Palm Springs or Miami Beach, Waikīkī isn’t known for its architecture. And yet, once upon a time, the area was the playground of the architectural vanguard. In 1957, one of Buckminster Fuller’s famous geodesic domes was built as part of what is now Hilton Hawaiian Village. The year before, George “Pete” Wimberly, who went on to design the Sheraton Waikiki—the largest resort in the world in 1971—gave Waikīkī its most iconic structure to date: the hyper-modern, tiki-flavored Waikikian hotel.

This was as bold as Waikīkī ever got, an outgrowth of post-World War II optimism and Hawai‘i’s increasing prominence in the American imagination. In the 1960s, advancements in commercial air travel shortened the flight time from the West Coast to Hawai‘i from nine hours to less than five, making the islands more accessible than ever. Between 1960 and 1970, visitors increased sixfold and began staying for shorter periods. This glut resulted in more utilitarian architecture and also changed what a hotel was. Large suites with full kitchens, once de rigueur, were no longer needed. Hotel rooms shrank accordingly and were perched higher and higher in the sky.

Many of Waikīkī’s iconic structures were torn down to make way for ever-larger resorts. The Waikikian closed in 1996, its fantastical lobby and restaurants demolished over the following years. Fuller’s dome, which had served as a nightclub and venue for performers like Don Ho, came down in 1999. Beachfront property reached such a premium that even tiny parcels were sold off for development. The sliver of land fronting St. Augustine Church, a relic of atomic-age architecture, became a Burger King and an ABC Store, severing the church from the street and beachfront.

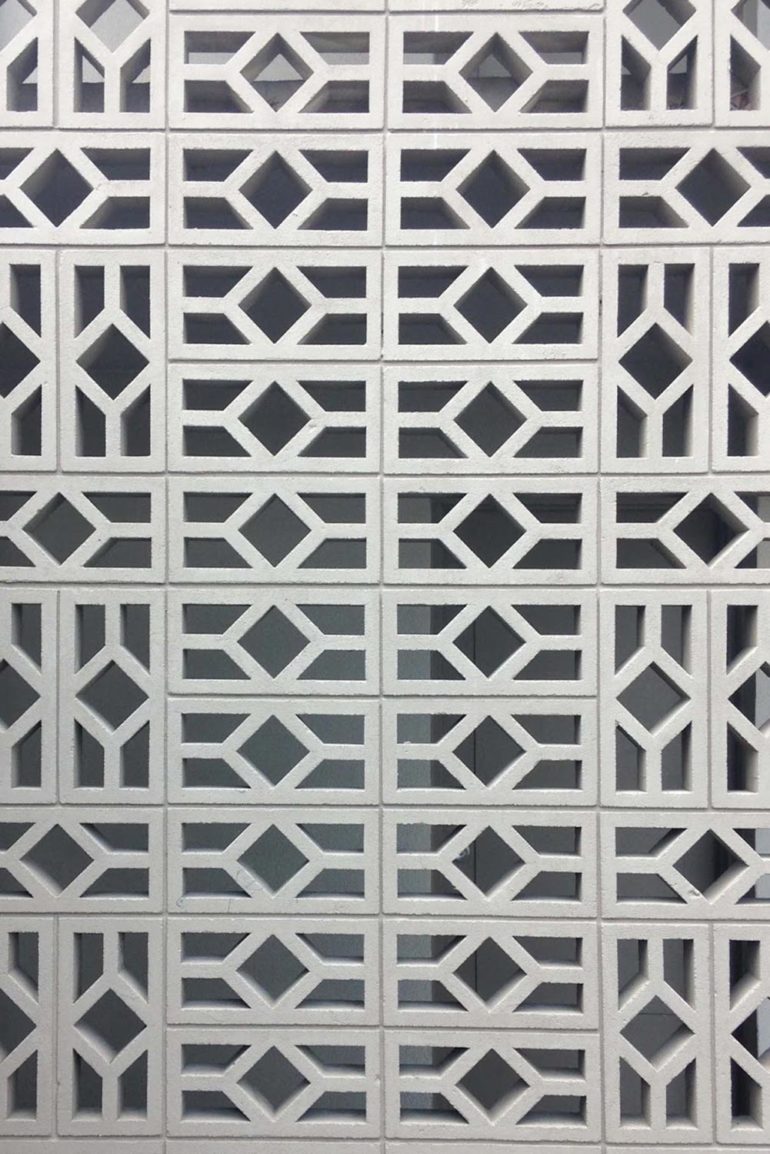

Still, a surprising amount of significant works remain. On Kalākaua Avenue, the arching, tessellated, Escher-like façade of Wimberly’s Waikiki Galleria Tower, built in 1966, sits next to Hart Wood’s Asian-influenced S & G Gump Building, which was built in 1927 and is now a Louis Vuitton store. Some of the seemingly unremarkable walk-up apartment buildings have architectural pedigrees of their own, like the uber-retro Darlani Apartments, designed by Lemmon, Freeth, Haines, and Jones, the same architects who would later help realize the Hawai‘i State Capitol.

The neighborhood’s railings alone could fill a coffee table book. They come in wood, steel, iron, and concrete and feature every pattern imaginable: leaves, sails, surfboards. They bend and wave and zig and zag. They are black, white, aquamarine. Like its ubiquitous breezeblocks or characteristic copper signage, Waikīkī’s banisters and balustrades are functional, yet they serve as stylistic flourishes. At the Kaiulani Court Apartments on the corner of Ka‘iulani Avenue and Kūhiō Avenue, a breadfruit motif is rendered in black wrought iron. Down the road, on Lau‘ula Street, a two-story building is adorned with subtle wood panels depicting banana leaves in relief. Along with lava rock walls and cantilevered lānai—hallmarks of Hawai‘i’s tropical modernism—the railings are symbolic of the designer’s wish to represent the beauty of the islands in the built environment. They give Waikīkī a sense of self.

Today, the old Waikīkī is seeing something of a revival. Building on a worldwide interest in midcentury modern design, boutique hotels have opened in rehabilitated buildings from the 1960s, generating a newfound appreciation for Waikīkī’s midcentury modern architecture. In 2017, the Queen Emma Land Company announced its plans to renovate the low-rise Beachside Apartments, designed in 1959 by pioneering local architect Ernest Hara, along with two other midcentury walk-ups on Kānekapōlei Street.

Like a song full of samples, Waikīkī defies easy categorization, serving up continually surprising textures and juxtapositions. The neighborhood is at its best when it embraces its disparate worlds and clashing styles. The old Waikīkī exists in pockets alongside every other Waikīkī that has come before and after it, and each Waikīkī that is yet to come.